The Invisible Landscape and Concrete Futures: A Solo Exhibition of Hazem Harb, Salsali Private Museum, Dubai. 3 March—1 September 2015

Contemporary colonialism—exemplified by Israel’s occupation of Palestine—asserts its hegemony through the manipulation of two key sites: historical narratives and physical infrastructures. The effacement of Palestinian presence on the land before 1948 constitutes a crucial part of the former strategy; the construction of walls and settlements that keep Palestinians within controlled, delineated spaces while expanding Israeli presence, combined with the destruction of existing infrastructure through regular invasions of Gaza, marks the latter. The combined power of the two tactics effectively denies Palestinians control over their own past, present, and future.

Hazem Harb’s exhibition, The Invisible Landscape and Concrete Futures, is a powerful interrogation of both these phenomenon, displaying stimulating inventiveness in its juxtaposition of nostalgia-inducing archival photographs and tough, sturdy construction materials, like concrete slabs and glass sheets. The exhibition consists of three separate series: Archeology of Occupation, TAG, and This Is not a Museum. All three employ mixed media to confront the ways in which archival and building material is de-faced and destroyed through Israel’s use of formal architectural techniques, especially the modernist use of straight lines, right angles, and meticulously streamlined blueprints and structures.

Hazem Harb, a Palestinian artist born in Gaza in 1980, who currently divides his time between Rome and Dubai, has consistently probed, through his various exhibitions over the years, the Israeli practice of constructing infrastructures and narratives at the expense of Palestinian lands and histories. In doing so, his art seems to borrow equally from the geometric foundations of minimal artists such as Sol LeWitt and the critical inquiries of histories of photography carried out by Black Atlantic artists such as Joy Gregory and Carrie Mae Weems. While the abundant use of white space and the conscientious execution of geometry are legacies of conceptualism and minimalism, the manipulation of photographic archives through color filters and cropping techniques brings to mind the radical critique of colonialist photography performed by Black artists in the Atlantic Ocean diaspora. Far from being derivative, Harb’s vision effortlessly blends the two approaches, providing a fresh perspective on the ongoing occupation of Palestinian land and identity.

Entering the main room of the exhibition, one is immediately thrust in the middle of slabs of concrete and blocks of solid color; the geometric shapes come together to form a dense, neat web, which represents the (literal) building blocks of colonialism. The first series, Archeology of Occupation, consists of evenly spaced rows of digitally manipulated photographs that cover the main room--all of them juxtaposing and covering Bauhaus-like architectural sketches with archival photographs of Palestine and Palestinians before 1948. For example, a photograph depicting a smartly dressed Palestinian family is only half-visible, hidden underneath a second photograph, which is layered on top of it, the second photograph evoking cracked and damaged concrete. Another frame shows an aerial view of a Palestinian urban landscape, cropped in a tidy, precise triangle, topped with a few blocks of concrete that rest heavily on the tip of the triangle. Yet another frame uses the photograph of a beach, semi-blocked by a strip of solid black, further obscured by sketches of triangles reminiscent of an architect’s sketchbook. The multiple layers frustrate the viewer, digitally intervening and interrupting the historic black-and-white photographs, only allowing partial glimpses, as if openly daring the audience to construct coherent narratives from censored documents.

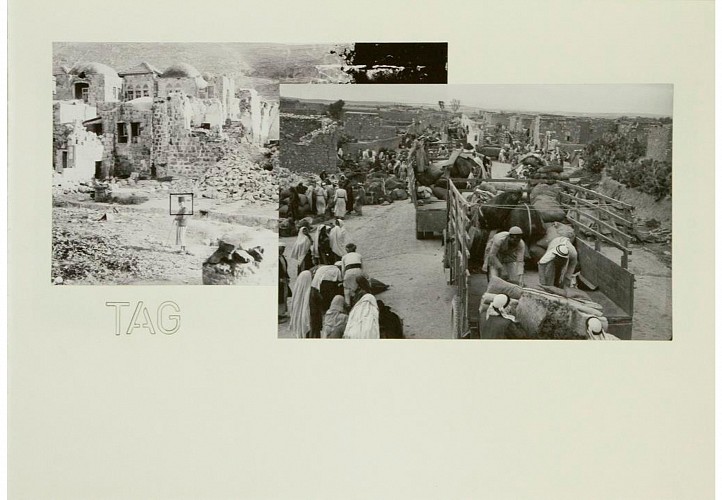

The second series, TAG, is another exploration of history through the digital manipulation of archival photographs. Here, family and portrait photographs dominate, the face(s) in each photograph marked by a thick, black square reminiscent of a Facebook tag. However, the conspicuous absence of any names, which would be expected in a Facebook tag, disorients the viewer, suspending her in a void emptied of any documentary information. Instead of identifying the individuals, presenting them to the audience, the squares seem to be referencing the absolute anonymity of the marked people, further highlighting their absence from the historical archive. One gets the feeling that s/he is flicking through an Internet without any hyperlinks, a museum emptied of all names, dates, and places—simply, an endless and useless text without any context. The unidentified individuals stare out at the viewer with adamant solidity, situated in a timeless, space-less existence. As with the first series, TAG becomes a pertinent metaphor for the erasure of Palestinian history, a denial of their presence on the land before 1948.

[Hazem Harb, Tag 21, from the Tag series, 2015. Image copyright the artist, courtesy of Athr Gallery.]

[Hazem Harb, Tag 21, from the Tag series, 2015. Image copyright the artist, courtesy of Athr Gallery.]

The third component of the exhibition, This Is not a Museum, abandons the techniques of photography to work within the three-dimensional and conceptual space of an installation. A platform—raised knee-high and erected in the center of the main room—carries a pillow, a sheet of glass, and a circular light-tube, all sparsely arranged on the platform, held in different positions by crumbling, half-blocks of concrete. At the head of the platform is a screen with a video loop: an inflatable bed rises slowly from a deflated position, pushing concrete off of itself, over and over again, like a domestic phoenix. The Sisyphian video, along with the jarring juxtaposition of domestic objects and rickety concrete, points at the bare and harrowing reality of Palestinian life: a vicious cycle of destruction and re-construction, a performance of the impermanence of identity and space that plays out with each successive Israeli invasion. Unlike the two photographic series, which focus on pre-Nakba photographs of Palestine, the installation engages with contemporary concerns, especially the space of the refugee and the diaspora.

[Installation view of Hazem Harb`s This is not a Museum, (2015). Image courtesy of Athr Gallery.]

[Installation view of Hazem Harb`s This is not a Museum, (2015). Image courtesy of Athr Gallery.]

One particular quote from an interview given by Harb before the exhibition opened is particularly striking. When asked, “Why are you an artist?” Harb replied: “The answer to that question involves the historic photographs of Palestine (before the Nakba) that are connected to my upcoming show at Salsali. As a boy, I used to beg my mother to take out black and white photos. I remember she kept them in an old Arabic sweets tin. This was my first feeling of nostalgia…” The image of the old sweets tin carrying the black-and-white photographs, and the attendant nostalgia, seems, at first, incongruous with the painstaking geometry and bareness displayed in The Invisible Landscape and Concrete Futures. But even when employing sharp, determined lines, which evoke order and authority, Harb manages to elevate the photographs of pre-Nakba Palestine to an altogether different emotive plane, teasing the beloved photographs from underneath hulking concrete, transforming them into a kind of rare treat only allowed on special occasions. Here, precisely, lies Harb’s brilliance as an artist: his ability to imbue violent straight lines of architecture with unmistakable pathos, and to infect ordered and occupied narratives with a nostalgia for pre-Nakba Palestine, critically reflecting, along the way, on the disrupted identities and territories which constitute contemporary Palestine.

Nostalgia, as a political tool, has often come under criticism from those who believe that History marches in a straight line towards ever-brighter paths of progress. Hazem Harb’s exhibition is a convincing rebuttal, reminding us to look back, concentrate, and remember—not unlike Klee’s Angel, who is, as Walter Benjamin pointed out, irresistibly propelled into the same future to which his back is turned, all the while witnessing the debris of the past piling skyward.